Ethan was born on November 9, 2010, in a small apartment, on Hillside Avenue, in New York, New York. He was our second son and was a healthy, happy, precocious and loving little boy. In 2013 our family moved to Los Angeles for Ethan’s mother’s job. Ethan had always had a raspy little voice, but by age 3 we’d noticed he was also developing a speech impediment. A friend, a Speech and Language Pathologist at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis, advised us to have him evaluated by an ear, nose and throat doctor, as part of preparing Ethan to begin pre-school. We were new to Los Angeles and an acquaintance referred us to Dr. Ali Strocker. Dr. Strocker examined Ethan and asked us to bring him back the following week for a more thorough examination. On that occasion she discovered Ethan’s right vocal cord, while healthy and developed, was paralyzed. She recommended he undergo an MRI scan to determine the health of the nerve that supplied the vocal cord. The day after Ethan’s MRI we received a phone call. The results of the scan were in, but the doctor needed to speak to us in person. “It would be best if you could come today,” she said. We sat in stunned silence as Dr Strocker explained the MRI had revealed a mass in Ethan’s pons, a portion of his brain stem. The doctor was not able to provide us with many details, but the underlying truth could not be denied. Ethan had brain cancer and it was very serious.

By sheer luck, Dr. Strocker was friends with Dr. Moise Danielpour, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Cedars Sinai medical center and she had already arranged for us to meet with him. Dr. Danielpour examined Ethan and then asked his grandfather, who happened to be visiting, if he could take Ethan to the waiting room. Dr. Danielpour placed one hand on each of our knees and gently but firmly let us know that Ethan’s cancer was the worst kind. They suspected is was Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG), an exceedingly rare pediatric brain cancer which is nearly 100% fatal. There are more than 300 million people in the US and fewer than 300 DIPG diagnoses each year. That means our boy was literally 1 in a million. It was May 20, 2014 when we learned Ethan was going to die and there was nothing to be done to save him.

Ethan’s case, however, was slightly different than most DIPG cases. By a cruel trick of nature, most cases of DIPG are only discovered in the late stages because children do not usually show symptoms until the disease is significantly advanced. However, because Ethan’s tumor was discovered “by accident,” in the earlier stages, Ethan’s case could be closely monitored and, hopefully, offer valuable insight into the disease. The MRI scans also revealed Ethan’s tumor included an exophyitic component, a portion extending out from the pons, which presented doctors with a unique opportunity to perform a biopsy. To operate would be dangerous, but after careful consideration and consultation with several leading experts in the field, we decided to go ahead with the surgery. Perhaps this biopsy could give us some real insight. Perhaps there was some slight chance this was all a mistake and Ethan’s tumor was not malignant. We held our breath and tried to come to terms with the likelihood the perfect, energetic, beautiful little boy, climbing from chair to chair in the waiting room, had less than a year to live.

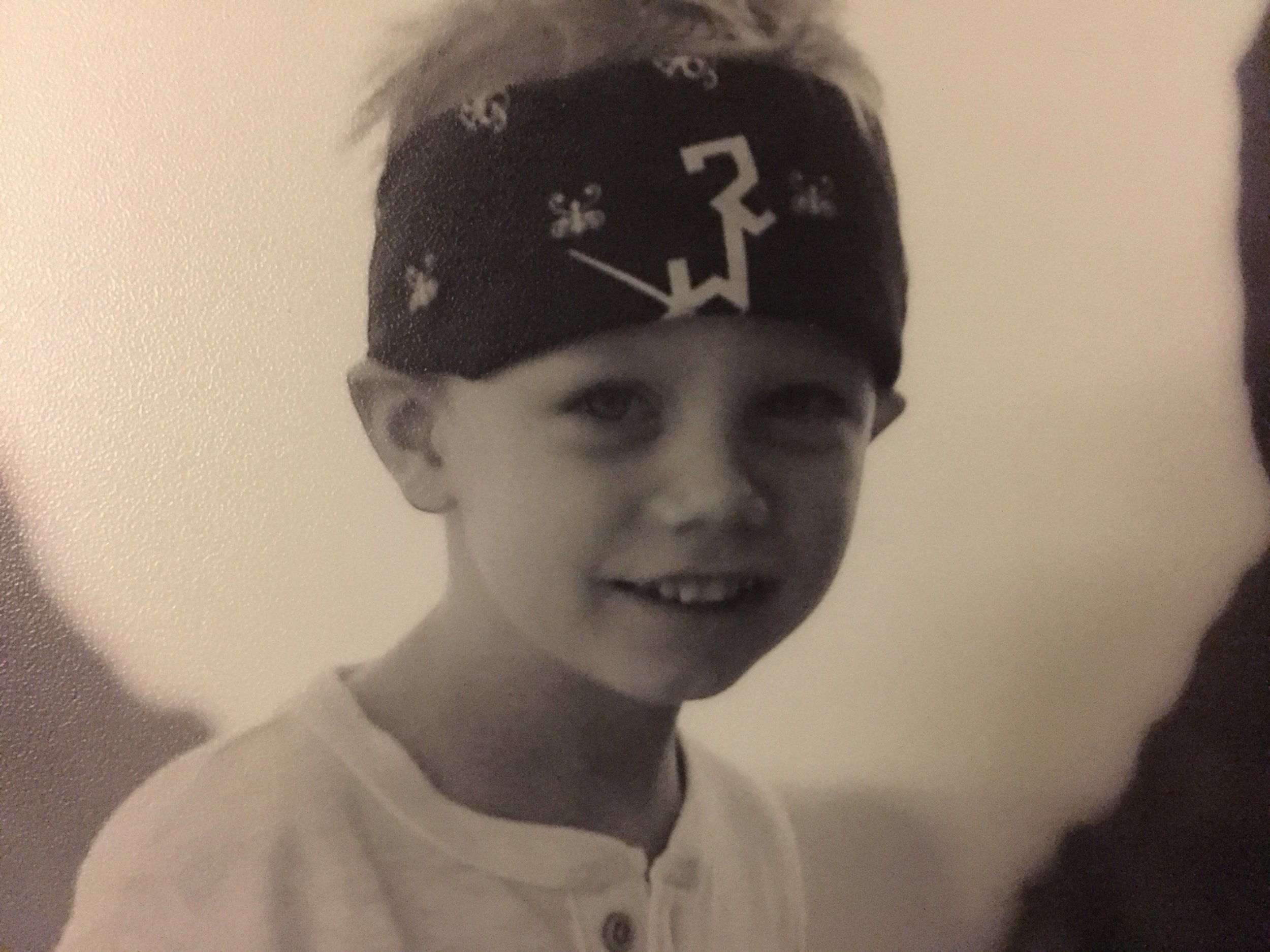

Ethan came through his surgery beautifully! The next several months were a whirlwind of exams, evaluations, scans, and recovery. Through it all Ethan was a model patient. He stoically endured blood tests, neuro checks, hair loss and an eight-inch scar up the back of his tiny head, another surgery to implant a chemotherapy port in his chest and countless hours of sitting and waiting. He was only 3 years old but met each challenge with a stoicism and perspective not seen in most adults. Ethan actually enjoyed a fairly normal summer with his brothers. There were visits to the beach and the Disneyland parks. A successful fundraising campaign made it possible for our whole family to travel home to Minnesota and Colorado during breaks in his chemotherapy regime. He spent valuable time with his grandparents, cousins and friends. He rode on the Durango-Silverton Railroad, visited our family farm in MN, drove tractors, rode horses, and made s’mores by a campfire.

That November we celebrated Ethan’s 4th birthday. His grandparents came for the celebration and his big gift was a new bicycle! Ethan continued his weekly chemotherapy treatments, complete with stops for ice cream treats after each infusion. We celebrated Thanksgiving and had a beautiful Christmas together. Then, on December 26, 2014, after a fitful sleep, Ethan woke up crying and could not be consoled. He was not able to keep his balance and his eyes were moving in different directions. The tumor had grown significantly and was blocking the flow of fluids in Ethan’s brain. We rushed him to Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, where he would undergo a second emergency brain surgery and spend the next 7 1/2 weeks fighting to stay alive.

Ethan made a miraculous, though limited recovery. Against all odds he learned to speak and swallow and even walk again. He played trains and watched movies and ate pizza with his brothers. He went to the beach and had donuts and even rode his bicycle again. He experienced an incredible Make-A-Wish trip to Disneyland, where he was treated like the prince of the kingdom! But, the recovery was not sustainable, and on July 30, 2015, Ethan passed away. He died at home, in Burbank, CA, in his parents’ arms, surrounded by family and the nurses who loved him, people he loved in return, people he inspired with his grace and courage and charm.

Ethan lived just 4 years, 7 months and 21 days. He died at nearly the same hour he was born. His life was brief but significant. He lived and loved with the heart of a lion and was loved beyond measure in return. He inspired doctors, nurses and therapists, who marveled at his resilience. His tissues and the tumor that killed him were donated to science and continue to be studied, offering valuable insight into the progression of pediatric brain cancers. The joy and laughter he brought to family and friends, even as he slipped further into the frailty of his illness, lives on. That love, that inspiration will be his legacy.